Today I’d like to provide two stellar reasons to take more time to study the other animal inhabitants of this extraordinary planet. For many centuries humans have told each other stories of beasts capable of instilling fear into even the bravest of individuals. Some of these tales may have been exaggerated versions of real beasts that people encountered; it’s certainly not difficult to imagine a 16th Century human attributing supernatural features to enormous animals they’d actually seen, but could find absolutely no rational explanation for. When knowledge of these elusive and sometimes terrifying creatures was unavailable, and it was likely that most individuals who would encountered one of these beasts would never meet another person who had, it’s easy to understand how the real events can get faded by folklore as time goes on.

One of the most important and attractive qualities of the scientific method of testing is that individual scientists are never granted authoritative power; that is, every scientist is equally subject to getting things wrong. Science reveals the natural world as it is; with no regard for the ‘feelings’ or ‘beliefs’ of individual, fallible scientists – regardless of their position within the scientific community. Evidence is required to persuade individuals deeply interested in finding out about the natural world as it truly is; rather than what they’d like it to be, or what they think may make for a ‘better’ story. In my opinion, modern science offers a much more wonderful alternative to the primitive, superstitious thinking of our ancestors who, by shear accidental placement in history, would accept a bunk theory over no theory at all. The folklore and mythology of our ancestors is extremely valuable for historical and literary purposes, and I would never wish to see the rich contributions of such creative thinking lost to pure rationality; however, there really is something exciting about developing an understanding of the natural world based on evidence rather than tribal affiliations, cultural traditions and insufficient supernatural non-explanations.

Although the fire-breathing dragons and ship sinking cephalopods of ancient folklore were essentially the result of a creative, several century long game of ‘telephone’ – I do have some news for you – DRAGONS and SEA MONSTERS are real! Well, kind of.

REAL DRAGONS:

Flying Dragons:

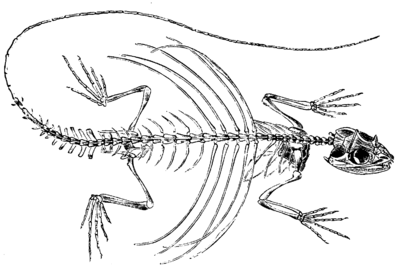

Flying Dragons, of genus Draco, are native to Southeast Asia on such islands as Malaysia, Singapore, Sumatra, Borneo and Palawan. The name is a bit deceptive, as they are not capable of true flight; rather, like some arboreal mammals, these reptiles are capable of gliding surprisingly long distances from one tree to another. Flying Dragons can glide several meters by stretching abdominal flaps of skin, with rib bones running through them and then using their tail to guide them while gliding; however, in order to achieve any real distance, the lizard must be fairly high up in the canopy. Draco lizards are only capable of gliding from high above – and the higher they are, the longer they are capable of gliding. When one of these phenomenal lizards is about to take off, they point their heads downward, in the general direction of their destination. They are incapable of these amazing gliding abilities in times of substantial wind or precipitation, but these fascinating creatures have adapted an extremely useful, interesting means of escaping their predators by taking to the skies when the weather allows them to.

Male flying dragons are highly territorial, often scent marking a few trees as their own and acting quite aggressively towards any other male dragons which trespass on their territory. Generally, each individual tree may house between 1-3 female dragons with whom the male dragon will mate. Similar to anoles and various other lizards, their aggressive display includes bobbing. Additionally, male flying dragons may also extend their membranous ‘wings’ (dewlaps) to make themselves appear larger; which is analogous to the throat dewlap extension of male anoles when they are behaving aggressively or territorially, see image below.

Flying dragons are similar to many other herptiles in their approach to hunting since they are largely sedentary, ambush predators; patiently waiting for unsuspecting prey to pass by them before they strike. This allows them to conserve energy and essentially have their food come to them. Draco lizards have a short, sticky tongue which they can quickly protrude and retract to capture their small, arboreal insect prey items (especially ants). They may be relatively small (generally less than 12 inches from tip of nose to tip of tail), incapable of true flight and unable to breathe fire; however, I find these miniature dragons much more interesting than the stuff of fables – precisely because they are real.

Next, i’ll discuss some much larger, but equally real, dragons that any rational person should be extremely cautious of – as they have a documented history of attacking (even preying on) humans!

Komodo Dragons:

Pictured above are Komodo Dragons; 3 meter long, 150 pound monitor lizards from the Indonesian Islands of Komodo, Flores, Palar, Rinca and Gili Montag. The saliva of these gigantic Varanid lizards contains a cocktail of really nasty, septic bacteria and toxic proteins which, when coupled with blood loss and shock of their prey animal, makes for an extremely effective means of predation. The bite itself is said to be extremely painful, and if left unattended, may result in the death of the victim. Although such instances are uncommon, it is not unheard of for a Komodo Dragon adult to attack, and even prey on, human beings unlucky enough to find themselves in a hungry Komodo’s path. Although the primary component of their diet is generally the small deer species which inhabit the same Indonesian islands, Komodo’s will sometimes eat wild boars, goats, birds, eggs, monkeys, carrion and even water buffalo! The bite of a Komodo Dragon adult would take a few days to kill the enormous water buffalo; however, groups of several adult lizards have been known to follow a bitten animal for days at a time waiting for it to become weak enough to kill and consume.

The forked tongues of these magnificent creatures are more commonly observed in snake species rather than in lizards; however, Komodo Dragons and other monitor lizards are also equipped with these fork tongues. Their tongues are flicked out, sometimes several times per minute, to gather multitudes of information about the animals environment. The sensitive tongue picks up the scent and taste of the environment before it retracts back into the animals mouth where it is delicately placed in the Jacobson’s Organ located in the roof of the mouth. The Jacobson’s organ is lined with a very sensitive tissue that processes information from the tongue and sends signals about the environment to the animals brain. This fascinating organ is what gives snakes and monitor lizards such an excellent sense of smell to find not only prey, but also mates! Females release pheromones to help males locate her when she is fertile and ready to reproduce – However, female Komodo Dragon’s are generally unreceptive to the males attempts and quite violently use their claws and teeth to thwart the males attempts to mate. If the male is successful, the female will lay a clutch of about 20 eggs that hatch after approximately 7-8 months. Young Komodo’s are equipped with an ‘egg-tooth’ which enables them to break through the leathery shell they’ve been developing in and, just like many other defenseless reptile offspring, most are eaten by predators before reaching sexual maturity.

Komodo Dragons have extremely strong claws, and are excellent climbers when they are young and small enough to have their bodies weight supported in the trees. Additionally, these enormous lizards are great swimmers; capable of diving up to 15 feet deep! Komodo’s aren’t long distance runners, but for short spurts they can reach a maximum speed of about 20 miles per hour – much faster than most humans can sprint! Along with the other monitor lizards, Komodo’s are regarded as the most intelligent reptiles on the planet. In lab conditions and at Zoological Facilities, varanid lizards consistently show a level of cognitive ability not seen in other reptiles. Monitor lizards are easily target trained, and some have been trained to recognize symbols and even ‘count’ to six! Finally, before I move on to our next real life beast, I want to touch on one of the Komodo’s most amazing qualities – Parthenogenesis!!!!!

Some of you are probably thinking, what the hell is parthenogenesis? Well, in short, parthenogenesis refers to the unlikely (but not impossible) biological phenomena which involves the reproduction of a sexually reproducing animal which has not engaged in sexual relations with another member of its species. Often, somewhat crudely, referred to as the ‘immaculate conceptions’ of the animal kingdom. In Wichita, Kansas in 2008 at the Sedgewick County Zoo the first documented case of parthenogenesis was documented among Komodo Dragons; though, there had been speculation and hints at Komodo’s having such an ability for many years prior. Instances of female parthenogenesis among Komodo Dragons result in all male offspring which, from an evolutionary standpoint, does make a lot of sense (since males usually leave more offspring behind than females). But how does this happen?

Well, we mammals have ‘X’ and ‘Y’ chromosomes whereas reptiles like Komodo Dragons have ‘Z’ and ‘W’ chromosomes. In mammals, a chromosomal combination of ‘XX’ means the individual is a female and ‘XY’ means the individuals a male. In Komodo Dragons, the combination ‘ZW’ results in a female individual and the combination ‘ZZ’ results in male individuals. Genetic Analysis of the offspring of the female Komodo (named Flora) at the Sedgwick County Zoo revealed that the Flora’s unfertilized eggs had been haploid (n), but went under chromosomal duplication without cell division (or fertilization via a polar body) to become diploid (2n) and begin developing into a baby dragon. When a female Komodo undergoes parthenogenesis, she is only able to provide her offspring with one chromosome for each of her paired chromosomes – even her sex determining chromosomes. This single set becomes duplicated via parthenogenesis within the egg and those eggs receiving a ‘Z’ chromosome will develop into ‘ZZ’ and become male whereas those who receive a single copy of the ‘W’ chromosome would result in the ‘WW’ combination, and thus fail to develop. For this reason, in the rare circumstance that a female Komodo Dragon reproduces parthenogenetically rather than sexually – it is possible to predict that all of her offspring will be males.

So now that I’ve told you about an excellent climber, swimmer, killer and thinker whose size and attributes should scare any rational person interested in approaching one in the wild; i’ll move to a quite different habitat to explain a very different kind of real monster.

REAL SEA MONSTERS

These marine beasts are truly the stuff of nightmares! Weighing in at nearly one ton and reaching a length of over forty feet, these enormous cephalopods are known as ‘Giant Squid’. Like other cephalopods – giant squid are intelligent, effective predators with a sensory/nervous system that excedes or rivals that of many mammals. As of now, little is known about these elusive beasts because of their habitat’s location. Giant Squid generally live in very cold, very deep waters and for many decades the only giant squids on record were carcases found by fishermen which rose to the surface. However, in 2006, a team of scientists off the Ogasawara Islands were able to document the first encounter with a 24 foot, living giant squid. The specimen was highly interested in the film equipment of the research team, as is demonstrated in the picture below.

Giant Squid Anatomy:

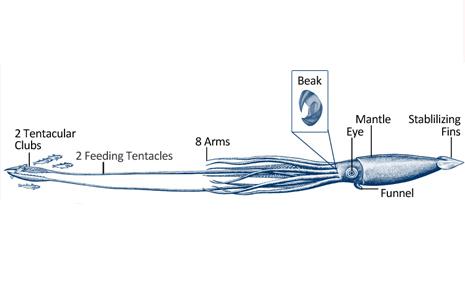

One common misconception about cephalopods is that they have 8 tentacles. In reality, cephalopods have between 8-12 arms, and generally two tentacles. The ‘arms’ are an evolutionarily modified, molluscan foot which is covered in paired suckers – up to 300 per arm. From a mammalian perspective we e can think of these arms as modified ‘lips’; which surround the animals mouth/beak. The tentacles are modified feeding appendages which help capture prey, and the animal can retract the tentacular clubs once they come into contact with an appropriately sized prey animal. The eyes of giant squid are the largest in the animal kingdom and are approximately the size of a dinner plate! The funnel is used to expel waste, locomotion via jet propulsion, squirt ink, lay eggs and exhale. The massive, extremely tough beaks of these marine creatures are quite similar to the beak of a parrot. The beak is used to slice manageable chunks of their (often still alive) prey, and then the radula (‘tongue’ like organ covered in chitinous spikes) is used to shred the large meat chunks into a digestible, ground material. Below is a picture of the fearsome cephalopod radula.

One of the most astounding facts about these creatures is that they are capable of attaining such an enormous size in a very short period of time! In fact, even giant squid are believed to live a mere 5-7 years maximum. During this time, these magnificent beasts will struggle to find food, shelter and mates – a vast majority of their molluscan offspring will be unfit to reproduce and will end up as a meal for a larger predator before ever reaching their characteristic, massive size. There are believed to be several species of these massive cephalopods in existence today, and a chart of their geographical distribution is below.

Finally, if you weren’t already creeped out enough by these huge animals – I will leave you with one more thought to ponder about the Giant Squid. The many suckers which line their arms are themselves surrounded in small, but extremely sharp, hooks! The suckers play the role of environmental sensory devices – sending information about potential food items back to the cephalopods central brain before deciding “I Want That!” If the food item is deemed worthy by the animals large, complex brain; the giant squid will quickly lock on to its prey item using the hooks which line the suckers on its arms and tentacular clubs, then pull the prey item towards its beak where the prey item animal almost certainly will meet a nasty fate. Below is a picture of a whales skin which had been grabbed by a giant squid. The circular sucker markings of these massive marine predators are extremely pronounced because of the hooks the giant squid dug in to its prey items skin.

Material References:

http://nationalzoo.si.edu/animals/reptilesamphibians/facts/factsheets/komododragon.com

www.LiveScience.com -Katharine Gammon, OurAmazingPlanet. 25 February 2013, 11:09 AM ET

Card, Winston C. 1994. Draco Volans Reproduction, Herpetological Review 25(2)

Michael Van Arsdale – http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Draco_volans

Cerullo, Mary and Clyde Roper. Giant Squid: Searching for a Sea Monster. Mankato, MN: Capstone, 2012.

Ellis, Richard. The Search for the Giant Squid. New York: Penguin, 1998.

Dr. Clyde Roper and The Ocean Portal Team: http://ocean.si.edu/giant-squid

Photo References:

Open Mouth Komodo http://djarn.edublogs.org/2010/02/18/komodo-dragon

Green Draco Lizard – http://www.flickr.com/photos/steven_wong

Flying Dragon in Action- http://timlaman.photoshelter.com/image/I0000ofEMiiSMm.wFlying Dragon Skeleton – Keith Edins, Skeleton of the Flying Dragon (Genesis of Species) 18, March 2007

Green Anole Dewlap- http://www.emptynestchronicles.com/tropical-backyard-buddies/green-anole-with-dewlap/

Komodo’s Fighting – http://natureandscience-alb.blogspot.com/2013/02/the-sex-life-of-komodo-dragon.html

Jacobsons Organ – http://www.rcreptiles.com/blog/index.php/2006/11/30

Komodo in Village – http://www.arkive.org/komodo-dragon/varanus-komodoensis/image-G6268.html

Komodo Hatchling – http://www.livescience.com/9460-female-komodo-dragon-virgin-births.html

Giant Squid and Scientist – http://www.toptenz.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Giant-Squid.gif

Giant Squid and Camera -Tsunemi Kubodera of the National Museum of Nature and Science of Japan/AP

Giant Squid Anatomy – Smithsonian Institution, http://ocean.si.edu/giant-squid

Giant Squid Dissection – http://museumvictoria.com.au/about/mv-news/2008/giant-squid-public-dissection-at-melbourne-museum/

Cephalopod Radula – http://depts.washington.edu/fhl/zoo432/floats/flfeeding/Katharina_radula.jpg

Giant Squid Distribution – Smithsonian Institution, http://ocean.si.edu/giant-squid

Whale Skin – In Smithsonian Report, 1916. http://ocean.si.edu/giant-squid